Clean AWS Development: Packaging for Explicit Dependency Inversion

Overview

For our first step towards a Clean AWS project we are going to start with the packaging of the code base. This has nothing to do with AWS and everything to do with maintaining a clean project. The dependency inversion principle is maybe the most important Clean Architecture principle when it comes to the maintenance, and testability of code. It pushes out all of the low level details of a project that end up quickly rotting and becomming legacy code, to the periphery so that they dont get stale during development and are easier to update once you have gotten past the greenfield phase of the project.

The easiest way to maintain the dependency inversion principle throughout the code base is to make it explicit through packaging. The packaging for the project will consist of the following: Common, Core, Adapters, Persistence, AdaptersImpl, PersistenceImpl, and Head. Packaging a project like this makes breaks in the dependency inversion principle observable through code reviews, commits, etc. Any time the principle is broken a package will need to be included in the package manager dependency list in a place that it shouldn’t be.

Package Structure

Common

Common is almost the same thing as a domain model. It’s like a more pragmatic Domain package. In Common you will have your your domain model, requests and responses from actions within the Core verticals, and any utilities or enums that are useful to have available throughout the code base. This is considered the most abstract of all of the packages. There is no logic in this portion of the code base save for methods on the domain classes needed to use the objects effectively. Common has no dependencies from any other code in your project, unless it is an even more general Common, like something that is used org, or company wide.

Dependency List [empty]

Core

Core is all of the business logic that exists within a specific service. It could be called Core, or Engine, both terms are correct, this is what is going to be driving whatever business use case there is have for developing the project. Core will depend on the models, and interfaces from Common, and on the interfaces from both Adapters and Persistence. Core is sort of like the intellectual property, or the “special sauce” of a project. It contains virtually all of the logic that occurs within a program.

Dependency List

- Common

- Adapters

- Persistence

Adapters

Adpaters packages are where the magic happens! This package along with the Persistence package are what builds the “moat” around Common and Core, allowing them to be freely developed. Code in the Adapters package is also on the highest level of abstraction and thus has no dependencies. Think of the Adapters package as wrapper interfaces for anything external that the code base needs to interact with. It could be auth, or another service, or anything really. Wrap the external code client with an interface defined in your Adapters source code. Then define methods on the interface for every use case you have with the external code. This does not need to be a one to one wrapping, you may execute multiple calls to the service or even wrap multiple services in a single adapter. This is you defining the language that your program will use to “speak” with another program. It is the dependency inversion principle happening in real time. The packages and this separation of Adapters and AdaptersImpl are what is going to keep your code base clean, easily maintainable, and testable. This is because the Core package will only use the interfaces defined in the Adapters package so all of the extraneous dependency management can be pushed out to a later date and happen in fewer packages.

Looking at a diagram of the directed graph that this creates, the Adapters package becomes a sort of connection sink. A node where multiple packages depend on it, but it has no outgoing dependencies. That breaks the connectedness of the dependency graph from a single rooted tree, into multiple dependency trees that can be compiled separately, independently and with fewer conflicts. This in effect creates less legacy code, with legacy code being that which is defined as: “something I don’t like working with because its difficult for reasons that aren’t due to the problem being solved.” and is the actual implementation of the dependency inversion

Dependency List [empty]

Persistence

Persistence packages are where the magic happens! The Persistence package(s) are just special implementations of the Adapters package(s). They really are the same, it’s just that persistence is ubiquitous enough, and often central enough to a project that Persistence gets peeled off into its own separate package to not bloat the Adapters package. Here you will define interfaces for your persistence layer. The interfaces define the logical actions that the persistence layer will need to be able to execute, think save, batchSave, list, etc.

Persistence is really near and dear to me because I view it as one of the fundamental mistakes engineers have made, myself included. Often times people see data as the central theme of a large program, and it is, but the actual storage of that data should actually not be a central theme and should not be developed first. Push persistence implementation work off as long as possible because it is difficult to undo, and is a decision that can be made later on when needs of data access have been further exposed through the Core package development. It really helps to view databases as just another [specialized] service, and to treat them as such, like evaluating between two third parties to handle Auth.

That is actually another reason why persistence is broken off into its own package, generally the adapters are third party code, whereas persistence often times is owned by the team doing the Core development work.

Dependency List [empty]

Implmentation Packages: AdaptersImpl and PersistenceImpl

The implementation packages are the other half of the dependency inversion principle in action. These are the “low level” classes that handle all of the implementation details that would otherwise sully the code base.

Dependency List AdaptersImpl

- Adapters

- Whatever client that needs to be interfaced with.

Dependency List PersistenceImpl

- Persistence

- Whatever database client that needs to be interfaced with.

Head

The Head package brings everything together, it is the “main” function of the project, the entry point, you name it. Head could be an api, or a website, or batch processing workflow. It is mainly comprised of the tool being used to do dependency injection, the classes used to build the dependency graph, and the step function workflows for tying together the actions of Core. Anything else in the Head package is for supporting the step function workflows by giving them permissions etc. The dependency injection is what gives the interfaces for adapters and persistence some legs by providing the implementation classes anywhere the interfaces are called for.

Dependency List

- Core

- Common

- Persistence

- Adapters

- AdaptersImpl

- PersistenceImpl

Package Structure Magic

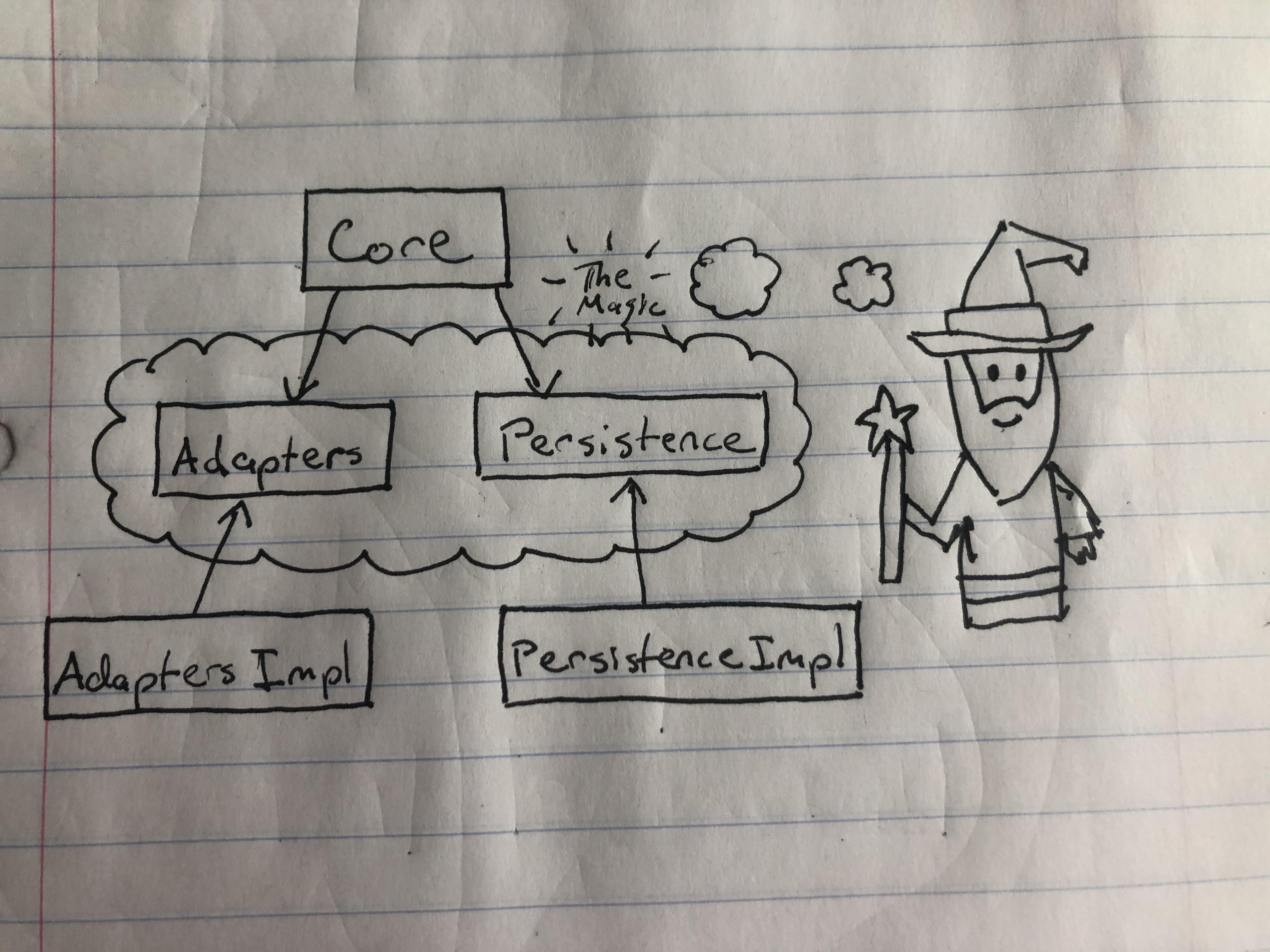

Let’s take a close up view of the magic that happens when code is packaged in a way to make the dependency inversion principle explicit. We will leave out the Common, and Head packages for now, because the real problem we are trying to solve is how to develop business logic in an unencumbered way. Here the dependency wizard gives us a pictorial view of dependency inversion via packaging in action:

What he has done with his magic wand/cloud is design all the interactions of his business logic with the outside world against interfaces held in Adapters, and Persistence. Then he made concrete classes for all of the interfaces and put them in the AdaptersImpl, and PersistenceImpl packages. Both the implementation and Core packages depend on the Adapters and Persistence packages, but the Adapters and Persistence packages do not depend on anything. This hard break in the dependency chain is what insulates the business logic from the outside world, and low level code problems that could take away from the fun of developing it. Now insulated, Core can attain close to 100% unit test coverage fairly easily, because all of the code in it is owned by the team developing it. In a later post we’ll have another look at the Wizard using the Liskov Substitution Principle and dependency injection to string everything together in the Head package to create a functional project.